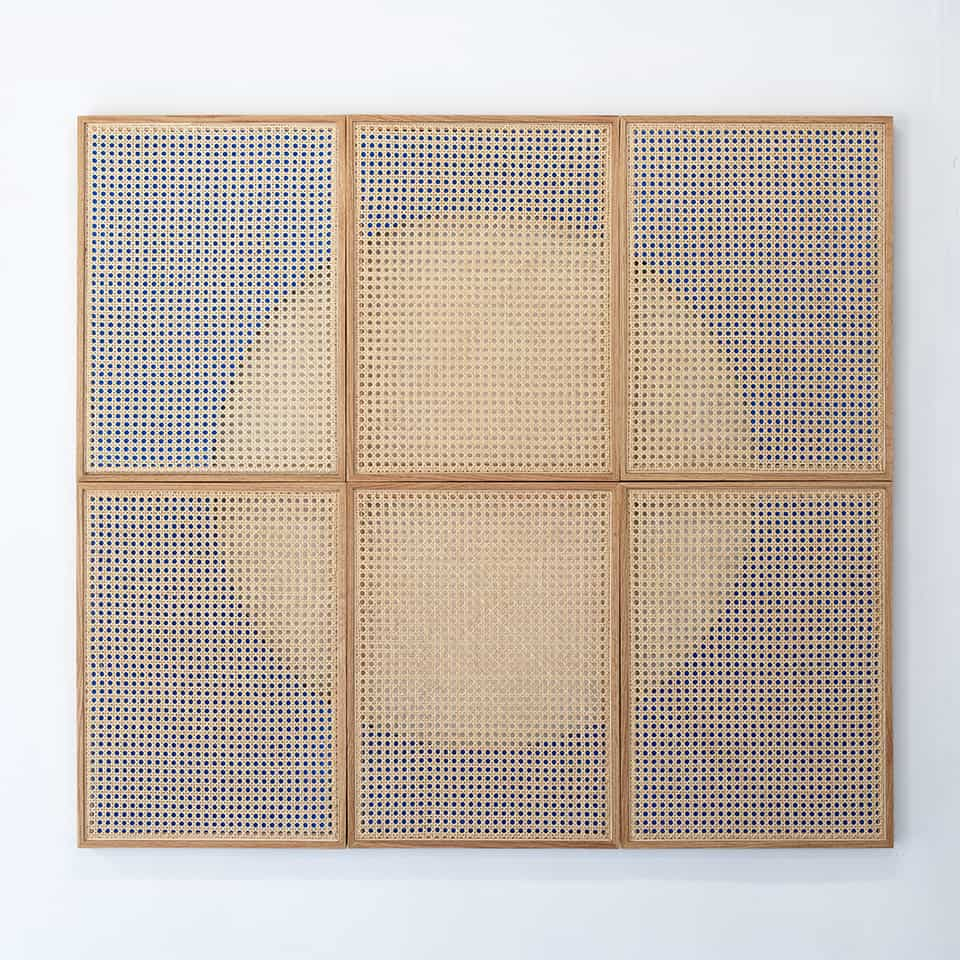

Mario Navarro

Vision In Motion, 2019

Cane webbing, wood, mdf, industrial lacquer

114 x 126 cm overall

Opening Saturday February 15, 2020 — May 11, 2020

PROXYCO Gallery, 168 Suffolk Street, New York, NY 10002

This exhibition focuses on a group of Mexican artists that lived and worked in the US as well as American artists that resided in Mexico from the beginning of the twentieth century to the present in order to dwell on the transnational character of their productions. By including works produced in the last century, the aim is to emphasize the continuity of this condition, creative exchanges, and circulation of ideas beyond borders. The transnational character of these works gives them a certain significance that cannot be understood in terms of any singular national context. They call attention “to the political, economic, and cultural relations that do not take political borders as their ultimate horizon, as well as to their criticism of the normative and exclusionary functions of nationalism”.[1] Within the histories of modern art of both countries, these sets of dialogues and relations began after the Mexican Revolution of 1910; that is from the 1920s. By the end of the 1930s, numerous American artists had traveled to Mexico to attest to the “Renaissance” of its arts, and some of them produced works there. Simultaneously, Mexican artists, particularly male muralists, received commissions for monumental works in the US as well as exhibitions in galleries and museums.

From a historical perspective, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco or David Alfaro Siqueiros might be the names that come to mind when thinking about these kinds of transnational dialogues, but the examples were numerous and involved artists from both nations. In the case of American artists, Grace and Marion Greenwood, Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish, and Isamu Noguchi made murals in Mexico whilst Alfredo Ramos Martínez and Jean Charlot made works in the US. Others like Rufino Tamayo and María Izquierdo resided and worked in New York. The case of Charlot is exemplary in the way in which he embodies an acute transnational, even global, consciousness. Born in France, he moved to Mexico in 1921 where he participated in the formulation of the muralist avant-garde. He was also a promoter of it through books and essays published in the US and elsewhere. He also continued a realist and muralist practice in the US after he established himself in New York in 1928.

After the end of the Second World War, and within the domestic and international contexts proper of the Cold War, several American artists settled in Mexico and continued to produce art that pursued certain social ideals and that was committed to realism. Elizabeth Catlett is a paramount example of this. In Mexico, she learned traditional and new artistic techniques, such as wood carving and linoleum printing, and created powerful political works regarding issues of discrimination and social segregation in the US. Within the same context of the Cold War, Canadian-Mexican artist Arnold Belkin was able to produce a realist mural in New York in 1972, bringing the postwar legacy of Muralism, and global realism, to the US. To execute his mural Against Domestic Colonialism, he worked and collected information from the residents of Hell´s Kitchen. For a committed postwar realist artist, such as Belkin, it was a triumph to create a community-based mural of this kind in the country that had been promoting abstraction as an “ideological weapon” during the Cold War.

Several scholars have remarked how New York, during the second half of the twentieth century, became a global epicenter of the arts; a condition that drove numerous artists from around the world to establish in the city. This phenomenon gradually paved the way for the articulation of a harmonious fin-de-siècle multiculturalism in discourses around art. Julio Galán was a young artist when he moved to New York in the mid-1980s. Born and raised in the conservative north of Mexico, New York offered him not only a vibrant art scene but also an established and openly gay community and culture. His work documented the anxiety and crisis brought by the AIDS pandemic that erupted around those years, through a style of figuration that placed him in line with late pop aesthetics and the neo-expressionism of Julian Schnabel or Francesco Clemente.

Contemporary artists from Mexico and the US continue to engage in this kind of geographical and cultural exchange. Livia Corona, for example, has developed works that revise the history of this sort of transnational connections. In Rx (Red and Yellow Kills a Fellow) (2015) she abbreviates the history of the silver industry in Taxco, Mexico, in connection with the development of its modern designs, a process in which some American designers and the market of tourism played a crucial role. Yeni Mao in his work fig 20.05 cabal (leo) (2019) alludes to the patio in traditional and modern architecture in Mexico, in particular as a situation of display for plants, ceramics and other forms of decorative arts. For this sculpture, which takes into consideration the solution of the base, Mao produced a piece of ceramic altering an existing industrial model, transforming a regular commodity into an intriguing and suggestive form. Mario Navarro´s Vision in Motion (2019) combines modern formal principles with traditional fiber works and hand-made solutions, in this case, the weaving of rattan often used in chairs and other kinds of seats. Beyond his artistic production, Navarro has promoted, like Charlot and other artists before him, the sort of transnational dialogues between artists and geographical and cultural contexts that are the focus of this show.

— Daniel Garza Usabiaga

[1] Rebecca M. Schreiber. Cold War Exiles in Mexico. U. S. Dissidents and the Culture of Critical Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, xii-xiii