ITZKAN

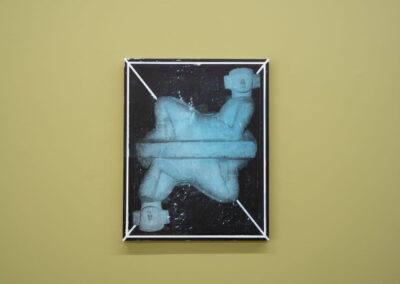

Image detail: Cenote, 2020

Opening Thursday, October 22, 2020 — December 23, 2020

PROXYCO Gallery, 121 Orchard Street, New York, NY 10002

PROXYCO and Embajada jointly present Itzkan, a solo show by Mexican artist Claudia Peña Salinas. The exhibition takes its name from the original combination of the Maya terms <itz>, which refers to knowledge, magic, and occult power, and <kan>, the word for serpent. Moreover, <itzá> is the appellation of the first Maya occupants of the Chichen Itzá area in Yucatán, one of the most visited archaeological sites in the Mexican peninsula and the premise of this exhibition. Through the creation of a series of distorted reflections, Peña Salinas reassesses the sacred ancient knowledge embedded in both built and natural landmarks across the ways in which these are portrayed as tourist destinations.

Twice a year, during the spring and autumn equinoxes, large groups of tourists gather in front of the Temple of Kukulkán to witness the descent of Kan, the serpent deity. The architecture of the pyramid under the sun casts a shadow and illuminates Kan meandering from the top of the stairway down to the ground. Also known as The Castle, the temple functions as both a calendar and an oracle—its position and proportions reflecting a profound understanding of astronomical phenomena.

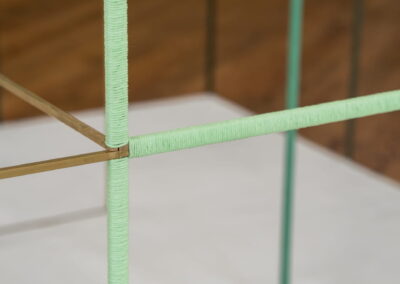

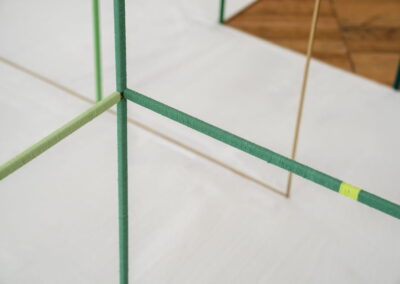

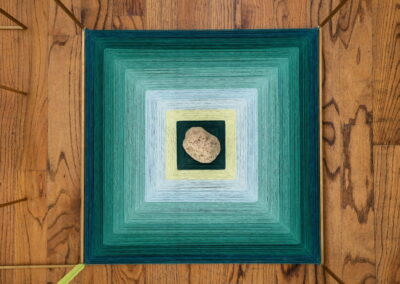

Inspired by this architecture, Itza is a large-format modular sculpture arranged like a pyramid. The structure consists of brass square frames woven together with hand-dyed thread, constructed in the same way as the other sculptures in the exhibition. For this particular composition, the modules are organized as cubes that unfold next to and on top of each other, gaining height through repetition.

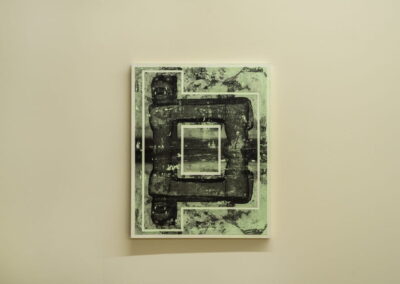

Meanwhile, Kukulkán is a series of seven image-transfer wax panels depicting the pyramid doubling as if reflected on water, a reminder of its proximity to bodies of water. The gradient of blue to green hues traces the movement of the sun, which illuminates some parts of the temple but compromises the visibility of others. Through this sequence of geometrical deconstruction, Peña Salinas points to the boundaries of the postcolonial capability to access and relate to indigenous consciousness.

In the surroundings of The Castle, the Sacred Cenote [sacred well] is another popular sightseeing destination of the area. Through time, the depths of the sinkhole have been extracted, looted, and despoiled of the treasures of their former guardians. Bones, pieces of pottery, jade, and other stones from the site are now part of ethnographic collections around the world. Meanwhile, tourists peek out from high points looking for an overhead view of the Sacred Cenote, only to encounter their own reflections: the excitement on their faces, the lenses of their cameras, their “expedition” hats. The water is a mirror to the outside that hides its complex history in abysmal darkness.

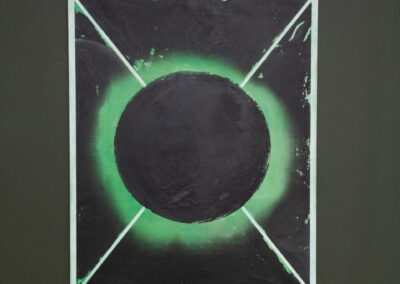

In relation to the work Cenote, the visitor’s gaze is a reflection of the postcard that crowns the sculpture itself. If this mise en abyme is overcome, the mysteries of the sinkhole make themselves accessible to the zenith perspective: four objects placed on the floor –the depths of the Cenote-sculpture. On the level of the dense green deep water, their reflections overlap and merge, a close likeness to a solar eclipse.

After meandering down the pyramid, Kan lies on the ground in the form of a luminous sculpture. The sacred serpent’s irradiant green light fills the space and exceeds the room. At a certain distance it mingles with natural light, creating the effect of a beaming pink glow. Like in its celebrated descent, Kan manifests itself through yet another phenomenological strike to the senses.

-Paulina Ascencio Fuentes